|

GENRES:

War memoirs; nonfiction

AUDIENCE:

Adults, teens; adult situations

SYNOPSIS:

Will Eisner spent a considerable amount of time either in the

military or working with them as a civilian contractor (he drew

a comics-style teaching magazine called Army Motors and

later developed P.S. Magazine). This book contains six

reminiscences from his various stints, which spanned World War

II to Vietnam.

- "Last Day in Vietnam" concerns an experience Eisner

had in Vietnam, where his job was to "visit field units

and pick up maintenance stories from automotive and armament

shops." Arriving at the camp "Bearcat," he meets

his escort, a cheerful, talkative major who brings him to a chopper.

The major is in very good spirits because this is his last day

in Vietnam, and he hasn't had a scratch. Along the way, the chopper

stops to pick up three sullen snipers, who are later unloaded

elsewhere. At the base camp, things quickly deteriorate when

the Viet Cong start attacking the perimeter. The major and Eisner

rush to the dispatch shack, but nothing's going out until morning.

The major's mood turns from cheer to despair; he's sure he's

going to buy it on his last day.

- "The Periphery" is a short piece, set in Saigon

and narrated by a "native guide," who points out the

behavior of the reporters in Saigon. They dispassionatly exchange

rumors and news, "like reporting a football match."

But two more come in from the field, having been covering Khe

Sanh, and while one tells the others about the action, the other

sits by himself, drinking. The war became much more personal

for him in Khe Sanh....

- "The Casualty" is entirely wordless. A wounded

soldier, sitting in a bar, bitterly recalls how he got his left

hand blown off--and it wasn't in the field, either.

- "A Dull Day in Korea" finds an impatient West Virginian

lieutenant itching for some real action. His unit is several

miles from the DMZ and doing nothing but patrols. As he reiterates

his life to Eisner, including tales of hunting with his drunken,

abusive father, he spies a "mommasan" cutting wood

on the hillside across the valley. He starts shooting at her,

but misses--and he can't figure out why another officer takes

his gun away just as he's drawing a bead.

- "Hard Duty" follows a real hard case in Korea:

a huge man who loves "killin'"--loves it too much,

so they transferred him to shop duty. After he's finished for

the day, he invites Eisner to come up the hill with him for some

"hard duty" that turns out to be quite a surprise.

- "A Purple Heart for George" is the only story that

came from Eisner's actual camp duty. George, a clerk, has a lover,

Benny, who's a combat soldier. Every Sunday night, George gets

drunk, regrets being a clerk, and writes up a letter requesting

a transfer to a combat unit. His friends, knowing that George

neither wants a transfer nor even remembers that he wrote the

letter when he sobers up, always make sure to tear up the request,

because the captain automatically approves all transfer requests.

However, his friends are both going away for extended periods,

so they enlist another clerk, Hal, to tear up the letter. When

they get back, they find that George has been shipped out--Hal

had been away on a three-day pass. "It was nobody's fault,"

says Hal, unconcerned. And the news out of Burma isn't good....

The book also includes a three-page introduction and historical

photographs in between each of the stories.

EVALUATION:

Is there anyone better than Will Eisner? The guy is almost 84,

and there still isn't anyone better than him. His artistic technique

never fails to take my breath away, even in small, subtle things.

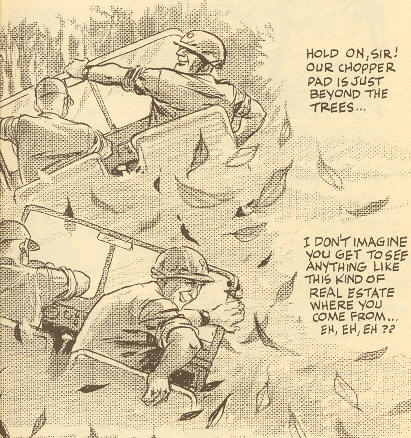

If you don't feel like you're moving right along with the men

in "Last Day in Vietnam" as the jeep lurches through

the jungle or the helicopter takes off, rises, and falls, you're

most likely blind. Note the composition of "The Periphery"

as the one reporter slowly starts dominating the panels, with

the others growing smaller and smaller until they fade away.

|

|

Lurch, lurch, lurch. |

|

Copyright 2000, Will Eisner |

He's pretty decent at understanding people too. The clueless

hillbilly in Korea, the major in Vietnam who goes from cheerful

to despairing to relieved, the quiet distress of George's friends

and the Khe Sahn reporter... in just a few pages the Master sketches

out fully believable people. He thus gives these short pieces

a great deal of depth.

My one quibble with the book concerns the narrative dialogue

in a few of the pieces, notably "A Purple Heart for George."

To explain the situation, the characters talk between themselves

about things they've known about for a long time, in language

better suited to conversation with strangers (i.e., the readers)

than to language in private. For example, when the two clerks

protecting George find his usual Sunday letter, one of them tears

it up ad says "He does this every weekend... doesn't even

know that he wrote it." They don't have to say this;

they know it. If they'e been doing this for some time,

they'd likely just look for the letter, grunt, and tear it up.

Since the conversation with Hal explains the same stuff in a

more realistic way, nearly all the dialogue during the tearing-up

scene could have been excised.

But this is a small point in an otherwise splendid work. Highly

recommended for those interested in wartime reminiscences; of

course, it's a necessity for Eisner collections and fans. I just

wish it was longer! Note that the roughest word in the book is

"crap" and there are no direct scenes of combat, but

this stuff may be too heavy for kids; probably too subtle for

them, if nothing else. Also, there's a bit of period racism,

used with tact--there's just enough to convey the flavor of the

times. |