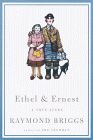

| Ethel & Ernest: A True Story. By Raymond Briggs. London: Jonathan Cape/Random House UK, 1998. 103p. $21.00hc. ISBN 0-224-04662-4. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. ISBN 0375407588.) |

|

GENRES: AUDIENCE: SYNOPSIS: Ernest worked as a milkman while Ethel kept house, and together they turned their house into a home, acquiring furniture here and there. Ethel remained a bit of a prude; when Ernest asked her to "come and try out" their new bed, she coldly replied, "Certainly NOT, Ernest! It's broad DAYLIGHT!" At age 37, Ethel finally got pregnant. The baby was healthy, but the doctor warned Ernest, "It was touch and go... there had better not be any more. More children... no more wife." So Raymond was their only child. Meanwhile, events progressed around them. Ernest followed the events in Germany, which baffled Ethel; they discussed the mysterious "tele-vision" that the BBC planned to start broadcasting; and they debated their place in society (Ethel constantly insisted that they were NOT working-class, but "tele-vision" was "all right for the gentry"). Soon their vague belief that all was well with Germany was rudely shattered when Hitler's armies marched into Prague. Ernest put blackout curtains up on the windows and sealed them against poison gas; the family also had gas masks. When war was irrevocably declared, the Briggs made the heart-wrenching decision to evacuate five-year-old Raymond to the country. Ernest soldiered on by building a bomb shelter in the garden and becoming a fireman; Ethel got a job packing parcels and was later promoted to clerk to work in an office (her dream job). Their house was damaged but not destroyed by bombs; "Could have been worse, Et," said Ernest. The war took its toll on them and their belongings, with the worst being a terrible 14 hours Ernest spent at the docks... "loads of dead... little kiddie--all in bits...." But they endured, and celebrated V-E day. With the war finally over, life returned to normal, with its pleasures, surprises, and disappointments. Ernest and Ethel reacted to the many changes in British society between 1946 and 1971, from washing machines and refrigerators to the merits (or otherwise) of the various Labour and Conservative governments that came and went. After 41 years in the same house, Ethel died. Ernest hung on for a few more months, his primary companion his black cat Susie. Finally, he too passed away, leaving Raymond to contemplate the sale of the house he grew up in, with the pear tree he'd planted from a seed not long after V-E day. EVALUATION: Aside from containing two splendid character studies, the book is also an interesting piece of social history. If you read a lot of history, it's easy to forget how peripheral "great events" and "great men" really are to the life of the average person. Ethel, for example, is underwhelmed by the Moon landing; she describes the gathering of moon rocks as "Just like kiddies at the seaside." And in the year 2000, with inventions and innovations the norm rather than the exception, it's easy to forget how strange and wondrous things like refrigerators were just forty years ago. Ethel in particular has a hard time with new things, viewing them with distaste and suspicion. And I'm no great expert on British culture, but the book seems to me to be an excellent illustration of working-class morals and beliefs: the inability of the characters to come out and say uncomfortable things (e.g., Ernest's fumbling attempt to describe homosexuality), the efforts to put things in their proper class (e.g., a tea room is too posh for the family, but Ernest's Cockney songs are too working-class), the sense that "it's not our place to know" what words like matriculation mean. (I can't help but compare the attitudes of the characters in this book to those of such writers as C. S. Lewis and E. Nesbit, whose characters were of the educated classes. Such a difference....) Boy, I tell ya--this book is so refreshing to look at after all that superhero and manga art. Briggs's painted art is technically adept, very easy on the eyes, and deceptively simple. For one thing, the faces of his characters are extremely expressive. Witness the pride on Ethel's face at Raymond's three art certificates, or the pain on Raymond's after his mother dies. The colors and lines are sharper in the early part of the book; things begin to soften, darken, and fog as Ernest and Ethel age. There aren't a lot of cinematic angles; the story is told mostly in the flat European style. However, Briggs does all kinds of creative things with words and word balloons, which really helps add emotion to the art. (If nothing else, he's one letterer who actually knows which words to emphasize.) I don't know why, but the graphic format seems to be ideal for biography. I've read my share of both text-only and graphic biographies, and invariably I'm touched more deeply by graphic ones. (Perhaps it's because graphic biographies tend to be about ordinary people to whom one can relate, rather than Major Historic Figures.) This one is an excellent addition to the canon. I highly recommend it for adults, especially those interested in social and British history. Teens and kids would likely find it dull. |

Return to Rational Magic Home