|

GENRES:

General fiction; crime & mystery fiction

AUDIENCE:

Adults, teens, kids; a few guns go off, but nothing much happens

beyond that

NOTE: This book won the 1995 Eisner Award (appropriate, eh?)

for Best Archive.

SYNOPSIS:

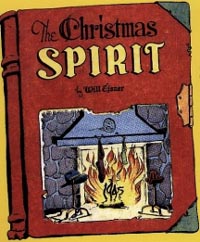

This book collects what were presumably the best of the Christmas-related

stories about Eisner's great creation, the Spirit. Spanning 1940

to 1951 (but skipping 1942-1944), the nine stories within only

use the Spirit peripherally, as he doesn't fight crime on Christmas,

preferring to let the "Christmas spirit" take care

of things.

- "Black Henry and Simple Simon" is the story of

two crooks who rob the "Paupers National Bank." Invited

into a church by a priest who bears a strong resemblance to Santa

Claus, the two baddies are overwhelmed by the poverty of a poor

child who eagerly anticipates his first taste of chicken and

his first-ever presents (the money at the bank was intended for

that purpose). The crooks return the money to the bank.

- "A Trilogy" concerns "three wise tramps"

who discover that the king of the hobo jungle is a bitter young

boy with one leg. To soften King Hobo, the three tramps tell

tales of Christmas and the minor miracles that happened to them

on that day. After the young boy falls asleep, the tramps collect

money to buy him a gift. King Hobo is so touched that he goes

to the Spirit to return money that he stole. The Spirit invites

him to share Christmas with him and his friends.

- "Horton J. Winklenod" is a wealthy man who still

believes in Santa Claus until other men tell him differently.

The millionaire, despondent, promptly vanishes. Two minor criminals

find him almost frozen to death in the snow. Gleefully, they

plan to ranson him for $5,000 and dump him in the basement near

a fireplace. Lo and behold, Santa comes down the chimney. The

millionaire is so happy to see Santa that he gives the criminals

the money they wanted.

- "A Fable" is the fable-like story of three ambassadors

who cannot agree on peace terms to end the war. One ambassador

is knocked out by a snowball and found by two criminals, who

take the man to the Octopus, "the greatest criminal in the

world." The Octopus wants the ambassador to continue to

block the Allied consolidation and promises to supply millions

of men to rekindle the war. Torn, the ambassador slips out. Meanwhile,

another ambassador is knocked out by a snowball; he wakes and

speaks with a despondent department-store Santa, who hates giving

out war toys as presents and has gone on strike. As a result

of these experiences, all three ambassadors promote peace at

the peace conference, and the world gives up war forever.

- "Joy" is a misnamed orphan boy in a war-torn country.

Scrounging for food, he encounters a starving old man, and Joy

gives the man his last bit of bread. The man calls himself Santa

Claus and promises to grant Joy's wish. Joy wishes to be "in

a land where the cities are not smashed and the buildings stand

tall and clean... where there are big stores filled to the seams

with toys and food and warm clothing...." But nothing happens,

so Joy falls asleep. The old man carries the boy to an airfield

and transfers his visa to the boy. Joy wakes up in the United

States.

- "Basher Bains" is a prisoner who hates Christmas.

Santa arrives and gives Basher his freedom, as well as his Santa

suit to wear. Though Santa expects Basher to return, the convict

has no intention of doing that. He digs up the loot he stashed

away before he went to prison. But as he's about to go off and

kill the Spirit for locking him up, three children come up to

him and ask for their present. Basher yanks off his beard to

show them he's not Santa, but one of the kids can't see--he's

blind, and the present they were hoping for is an operation to

restore his sight. Humbled, Basher takes the kids to a doctor,

hands over the money, and goes back to his cell.

- "S. Kringle Klaus" has come to the city to make

lists of what people want for Christmas. A snowball to the head

removes his memory; he wanders the streets trying to recall his

purpose. Two crooks blunder into him (hitting him on the head)

and, fearful of being caught, carry his unconscious body with

them. Santa wakes recalling everything, and after convincing

the thugs of his identity, he enlists their help in handing out

gifts.

- "Darling's First Christmas" tells of a very wealthy,

very unpleasant little girl, Darling O'Shea, who has never received

a gift. Curious as to why poor children seem to be much happier

than her, the sycophantic adults around her explain about the

concept of gifts and Santa. Though she views gifts as "charity,"

she nevertheless writes Santa a long legal letter demanding one

(1) gift this year. Receiving no answer, she hires men to guard

every home in the city and prevent Santa from giving anyone a

gift. "Shoot to kill!" she insists. However, Santa

arrives that night--he'd been unable to approach her before because

of all the guards surrounding her in previous years--and gives

her several years' worth of gifts. As he leaves, shots ring out!

But no one is hurt, and Darling is happy.

- "Joe Fix" is approached by a mysterious man who

demands that Santa not give out presents this year. Joe promptly

embarks on a smear campaign that turns the jolly old elf into

an evil villain, and Santa decides not to appear. But when Joe

gleefully looks at the million-dollar check given him by the

mysterious man, he sees the name "Lucifer Mephistopheles."

Realizing he's been tricked into doing the Devil's work, he gives

his check to Santa, who embarks on his annual mission after all.

The book begins with a short introduction by Eisner (who is

Jewish, of course) about his rationale for writing these stories.

EVALUATION:

It's disappointing when I read something like this by one of

the seminal figures in comics (hey, he invented the term "graphic

novel," which makes him a demi-god in my eyes, at least).

As might be evident by the synopses, these are secular, slight,

wistful, occasionally creative, mostly saccharine stories that

are only peripherally indicative of Eisner's storytelling talent.

Of course, Christmas stories in general are like that, and these

pieces are taken out of context--they were, of course, framed

by standard Spirit stories, so the saccharine didn't go into

overdose when they were first published. Still, the blurb on

the back of the book promises more than the stories deliver,

claiming that they're "filled with insights into the human

spirit." To employ a Yiddishism: balt. (It's a polite

way of saying "bullshit.") These stories are about

as insightful as greeting cards. But I shouldn't hold marketing

twaddle against Eisner, whose introduction expresses a sincere

admiration for that mythical thing called "Christmas spirit"

and whose stories attempt to capture it, however simplistically.

Actually, this book is more interesting to me for its incidental

depiction of the evolution of Eisner's artistic and narrative

style. The first story (1940) is crude; the characters barely

resemble the figures we've come to know and love, and the visuals

are conventional. A year later, Eisner had begun to experiment

with alternative forms, going outside the traditional panels

a little, though still feeling his way around the regular characters.

The jump to 1945 takes us into an era where Eisner obviously

had become much more confident with both his art and his storytelling.

The stories peak from 1946 to 1950. 1951, however, is pretty

bad, because the style simply isn't Eisner's, despite his name

on the story. I'm no Eisner historian, so I'm wondering if it

was "ghost-drawn" by someone else. Two other artistic

problems: these stories were taken directly from the old newspaper

versions, so they're often very grainy; and in several of the

stories, the word balloons sometimes point at the wrong characters.

According to the book, much of this material has never been

collected before (I've seen "Basher Bains" elsewhere),

so for that reason alone it deserves a place on the shelves of

Eisner aficionados. As a Christmas book, it's as good as any

other, storywise, and vastly superior (for the most part), artwise.

However, for people wanting to be introduced to the master, this

book isn't the place to start. Also, a word of warning: most

of the stories use the (to put it kindly) broadly drawn character

of Ebony, whose personality and the Spirit's treatment of him

may have transcended stereotypes, but his appearance and dialect

(especially in brief) sure don't. In historical context it's

tolerable, but I can see it offending people who just glance

at the book. Anyway, the book is out of print, but if I could

get one, you can too. (Hooray for the Internet!) |